We Are The Sabbath People

Meet Emily T. Wierenga

She’s an award-winning journalist, a columnist for the Christian Courier, a blogger, and a commissioned artist. In 2014, she was used by God to establish The Lulu Tree Foundation, a nonprofit that operates in villages around the world, equipping families to become sustainable through the local church.

She wore Sunday like some women wear hats, so elegant and confident, with a bold ribbon. She wore Sunday every day, in her silver curls and her sensible heels and her kind eyes. Eyes that crinkle when she smiles. The kind of eyes I imagine Jesus has.

She wore rest. A Sabbath rest that wrapped around my nine-year-old frame in a hug and let my muscles relax, for just a minute. Because being a pastor’s daughter was hard work and required utmost attention. I had to sit rigid on the hard pew and not talk, or Mum might give me the look that said she was disappointed and tired of being disappointed, and then I would need to try to pay attention to Dad’s sermon and not swing my legs. My brother and sisters were watching me, Mum would say, and I needed to set a good example.

So I sat straight and still and wondered things like, what would happen if I stuffed all the tiny pieces of communion bread into my mouth at once? That was probably a sin, but what if I was really hungry for Jesus? Could I ever be full of Him? And what about the grape juice that stained the corners of my lips like a mustache? How was it His blood, and why did we get so little of it? Why the tiny chalices, when the first miracle was about water turning to wine, and I was pretty sure they didn’t use tiny cups at a wedding. Wasn’t this like a wedding, and shouldn’t we want more of Him, not less?

The tiny communion cups reminded me of breakfast with its half glass of orange juice and half cup of granola measured out for us, and don’t talk unless you’re spoken to. But sometimes I just wanted to sing. I wanted to sing really loudly at the breakfast table and drink an entire pitcher full of orange juice and not measure anything ever again.

Those were the days when Auntie Gladys came into our lives and let us do all those things. She was the one who wore Sunday with grace. She wasn’t really my auntie, but she adopted me and my family like we’d always been hers. She became for me what the Sabbath might look like, if it were a person. She always seemed to be laughing, or on the brink of a laugh, and that’s a place where others feel wanted and free. That’s a place where a young girl can start to believe maybe church isn’t all bad, if people like Auntie Gladys attend. And maybe, just maybe, Jesus is Someone who likes to laugh, too.

We baked bread in Gladys’s kitchen and had tea parties at her table and picked fruit from the orchards. After supper, Uncle Joe would pull out the fiddle, and music filled their house like I wanted to be filled forever. The songs followed me home until one day when I stopped being able to hear them anymore. The sitting still and the measuring and the rules crowded everything else out, and I started to push back. I started to say No. I said it very quietly at first, when Mum tried to dish up my supper, and then I began to say it louder and louder over the next four years until it became more of a shout, and all music had been forgotten. I was skin and bones, and I had no more songs.

I think Church is meant to be worn like a festive hat, but sometimes it looks like the tassels of the Pharisees, hanging down long with their faces even longer still. There’s no rest, only religion, and this kind of church is the kind that picks on Jesus and His disciples for picking grain. It scorns the man whose hand was healed, and it resigns communion to a tiny cup and a dry cube of bread. And all that’s left is a gaping hole in the soul.

But that’s where the Sabbath people need to step in.

That’s where we need to come in, friends.

Knowing and declaring that “His works have been finished since the creation of the world.” (Hebrews 4:3)

We can rest and sing, because there’s no more work to be done except to believe. Jesus has done it all, and now, we are free to laugh and rejoice because It is finished.

The Sabbath is a large chalice overflowing with the wine of abundance. It is the Bread of Life, broken, and forever filling.

I had a dream a few years ago. I was in a church building, in a dark basement, and all around me were potted plants that had no sunlight. I knew I needed to get the plants outside. So I began to sneak them up the stairs, ever so quietly. On the landing of the stairs was a little girl who was holding a musical instrument she wasn’t allowed to play, and when I walked past her, she took my hand and came with me. We were stopped by an angry-looking priest who yelled at us. I quickly hid the plant. When he turned his back, we snuck into the light.

The plants were God’s children, and they were suffocating in the darkness of a religion that can’t hear the music anymore. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

I love the church, friends. I believe in the church, and attend one now, with my husband and three children. I attend it knowing it to be what it is – a shadow of a thing, much like the tabernacle. What we see now, we see dimly as in a mirror a beauty we will one day see face to face. (1 Corinthians 13:12)

But what would it look like for the church in all her brokenness to be full of Sabbath people now? I want to wear Sunday every day and invite the hurting and hungry into light, rest, laughter, and music. When they look at me, I want them to see the Jesus whose eyes crinkle when He smiles. He’s prepared a feast for us. Let’s open our mouths wide and then see what the Lord will do.

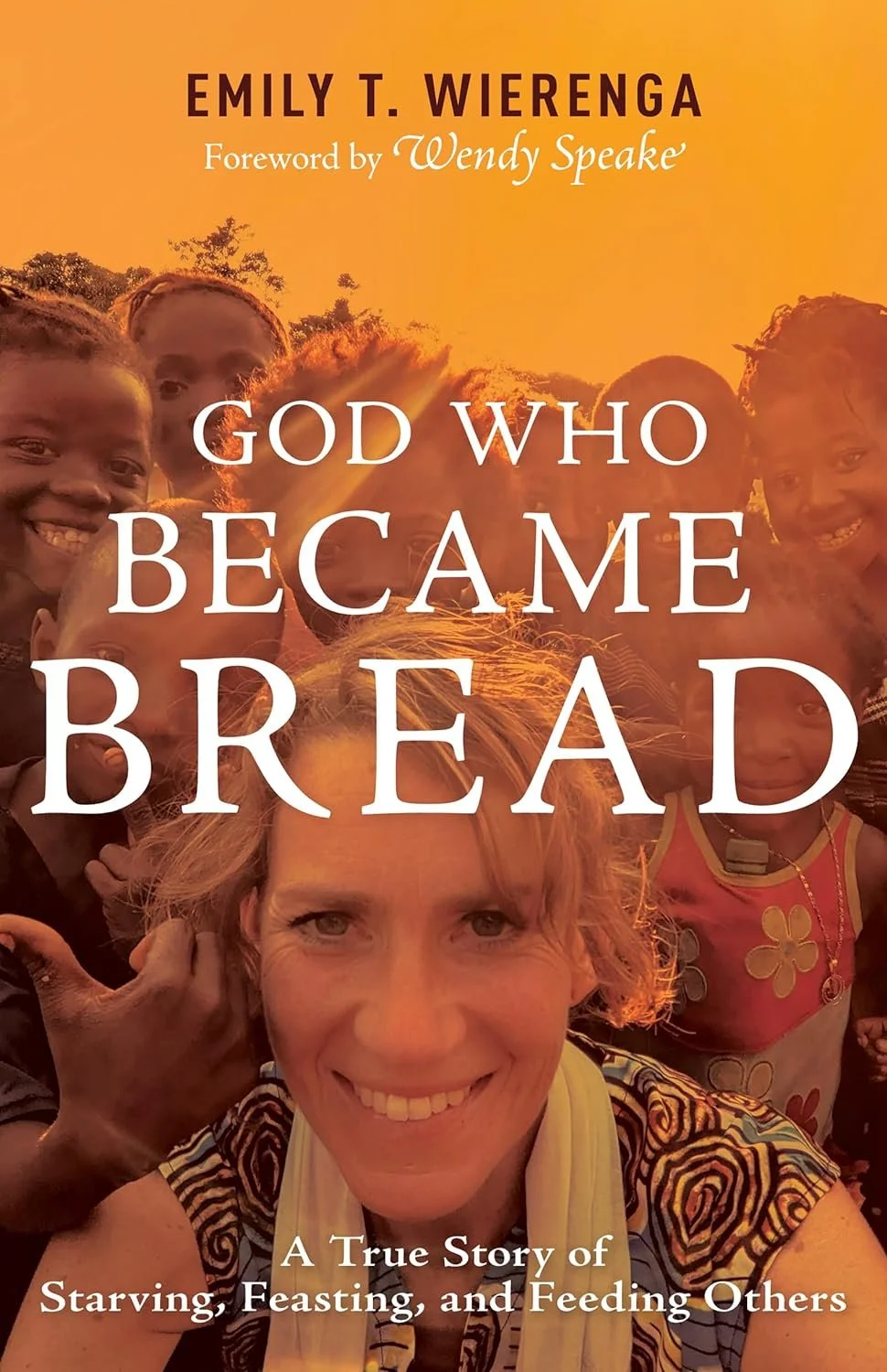

In this memoir described as “poetic, raw, and achingly beautiful,” Emily T. Wierenga takes readers on a vulnerable literary journey.

A former anorexic who nearly starved to death, Emily longed for more—the more she’d glimpsed during her childhood in the Congo, surrounded by vibrant faith. All she had now was dry religion. She craved a Communion that was more than an empty ritual.

It would be Emily’s return to Africa that would bring her healing. Unexpectedly, it would be the poorest of the poor who would lead her there. Emily exchanged her deep struggles with food for a growing discovery that the God of inapproachable light “dons an apron and prepares us a banquet.”

All who are broken—come to the table. Break bread with Emily, and feast on the God Who Became Bread. You will never go hungry again.